What is lactose intolerance and can it be cured?

Table of Contents

- People with lactose intolerance are at risk for poor health

- What is lactose?

- What is (and is not) lactose intolerance?

- If not lactose intolerance, what is causing my problems?

- How much lactose is too much?

- Your Low-Lactose Dairy Options Chart

- What causes lactose intolerance?

- Lactose intolerance is related to your country of origin.

- Your microbiome can help you cure lactose intolerance.

- Avoiding milk and other lactose-rich foods may bring on lactose intolerance.

- Lactose intolerance can begin after a tummy bug.

- Jeremy Lin used dairy to grow taller.

- Epigenetics and the lactase persistence “gene.”

- Your DNA is smarter than you think

- I heard dairy causes osteoporosis. Why do you recommend it?

- Why do some people develop allergies to food proteins?

- Do you need dairy in your diet if you don’t like it?

People with lactose intolerance are at risk for poor health

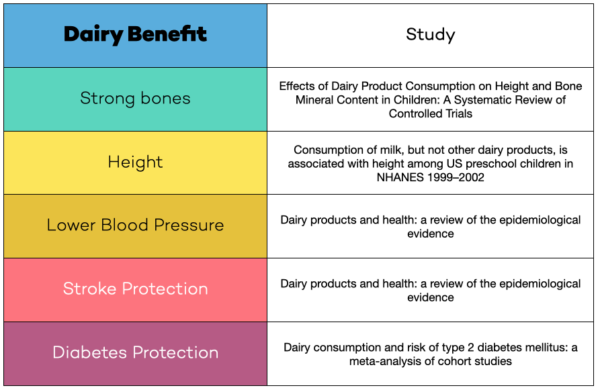

Milk, cheese, yogurt, and other dairy products are nutrient-dense, convenient, and delicious. I’ve found that people with lactose intolerance often assume they have an allergy to dairy and avoid all these wonderfully healthy foods even when they don’t need to. Since research shows that dairy avoiders are predisposed to osteoporosis and fragility fractures, it’s important to understand what you do and do not need to avoid. If you are one of the sixty percent of Americans with lactose intolerance, you might be able to cure the intolerance! And this article will discuss three things you may not know:

- Lactose intolerance is not the same as an allergy to milk and dairy

- Many dairy products are naturally lactose-free, and won’t cause symptoms

- Lactose intolerance can be temporary

And we’ll also cover these topics

- What is lactose?

- How do I know if I’m lactose intolerant?

- If I am lactose intolerant, how dangerous is it to eat foods with lactose

- What dairy products can I eat and still avoid lactose?

- I heard dairy can cause osteoporosis. Why do you recommend it?

Let’s start with a simple question:

What is lactose?

Lactose is the main type of sugar in every kind of milk there is: cow, goat, sheep, camel, mommy, etc. Interestingly, human milk has fifty percent more lactose than cow’s milk. Cows, sheep, buffalo, and goat all have very similar amounts of lactose, with cow’s milk having the most and goats the least. But these numbers are variable and it depends on what the animals had been eating. This is even true with human milk.

Lactose is a compound sugar.

To understand why some people are intolerant it helps to know that lactose is a compound sugar, meaning it’s composed of two sugar different types of sugar molecules stuck together, called glucose and galactose. In order for your body to absorb lactose sugar molecules into your bloodstream, the two must component sugars must first be split apart. That’s where lactase, the enzyme that snips apart the two lactose sugar molecules, comes in. Without this enzyme some people–but not all–experience symptoms of lactose intolerance when they drink milk or eat foods with high amounts of lactose.

Lactose is not the only compound sugar in our diets. Table sugar is also a compound molecule composed of two different types of sugar molecules, those two called glucose and fructose and we call the combination sucrose. Sucrose is the most common sugar in almonds, soy, and oats–the three most popular non-dairy milk of the moment. If people lose the enzyme that breaks these apart, they will develop symptoms identical to those of lactose intolerance.

What is (and is not) lactose intolerance?

Lactose intolerance refers to discomfort after consuming lactose that occurs due to low amounts of the enzyme lactase. When you lack the enzyme lactase, then your body does not break down and absorb lactose, for reasons described just above, so it stays in your intestine and can cause symptoms.

The excess sugar may make you retain excess water or it may be metabolized into excess gas by your microbiome. Both of these can distend your intestines and cause all the typical symptoms of lactose intolerance.

In addition, too much sugar may also feed pathogenic microbes that cause symptoms by disrupting the normal balance in your microbiome. We do not really know what kind of symptoms this may cause since we’re just learning about the microbiome.

Lactose intolerance feels like:

Symptoms of lactose intolerance include cramping, bloating, nausea, or diarrhea. When improperly digested, lactose can draw air and fluid into the small and large intestines. The extra stuff distends your intestine in an uncomfortable way. Fortunately, because lactose intolerance is not an allergy, it almost never has serious consequences and almost always causes short-lived symptoms.

If you have lactose intolerance the symptoms usually start within 20 minutes to 2 hours after consuming lactose-rich foods. The more lactose you eat, the sooner your symptoms start, and the worse they get.

The foods highest in lactose are milk, and buttermilk, which have about 12 grams of lactose per cup. Lactose is added to ice cream in varying quantities, and some brands have as much as milk; 12 grams per cup. On the low end are brands that have only 4 grams per cup.

If your symptoms are severe, you probably have a different issue.

Digestion always involves pulling extra fluid into the intestines and the development of bacterial-produced gas. This is not supposed to hurt. It turns out that many people with lactose intolerance are also more sensitive to normal intestinal processes. We tend to lump people who have this issue into the category of irritable bowel syndrome.

We really don’t understand irritable bowel syndrome very well, but that doesn’t mean you can’t do anything to improve your life. I can tell you that strictly avoiding seed oils, and cutting back on sugar and refined flour, always improves people’s digestive function significantly.

If your symptoms include skin rash, wheezing, or joint pain, that’s not lactose intolerance.

Lactose intolerance is not a serious condition and symptoms are limited to the gut. It is not an allergy to dairy. If you have symptoms outside the gut you may have an allergy or even an autoimmune disorder. And it may have nothing to do with dairy. Diagnosing the problem on your own is very difficult, and I can help you, as can many experts, if you have not gotten anywhere on your own.

Blood IgG tests do not diagnose lactose intolerance–or much of anything.

Food allergy blood tests that are IgG based are not helpful and many medical and scientific societies stress they have no role in diagnosing food allergy. This is because the immune system is very complex and having IgG often simply means you’ve eaten the food for a long time. In my view, they are a waste of money and should be taken off the market.

If not lactose intolerance, what is causing my problems?

If you’ve just read the above section and no longer think you have lactose intolerance, you may be wondering what else can cause issues with dairy. There are a few broad categories:

- Milk protein allergy

- Milk protein allergy that has triggered one or more autoimmune reactions

- Hypersensitivity to the hormones in milk

- Hypersensitivity to the bioactive peptides in milk

If your symptoms are severe, it’s important to work with a health professional with the following skill set: 1) An understanding of the role of seed oils in causing intolerance and autoimmunity 2) An understanding of how milk’s hormones, bioactive peptides, and amino acids are metabolized and how your body may be affected when the metabolic process goes haywire. Sadly, there are probably very few such practitioners floating around, so yes I would be delighted to help you myself.

How much lactose is too much?

Lactose intolerance is not an all-or-none kind of thing. In other words, some people with lactose intolerance do fine with small amounts of lactose. The amount it takes to trigger symptoms can even vary day to day depending on what else you’re eating and on your microbiome.

Adding to the confusion in sorting out your symptoms, lactose-containing foods contain varying amounts of lactose. A cup of milk contains between 9 and 12 grams of lactose. A cup of yogurt has about half of that. Cottage cheese may have as little as 0.8 grams per cup, or as much as 12.

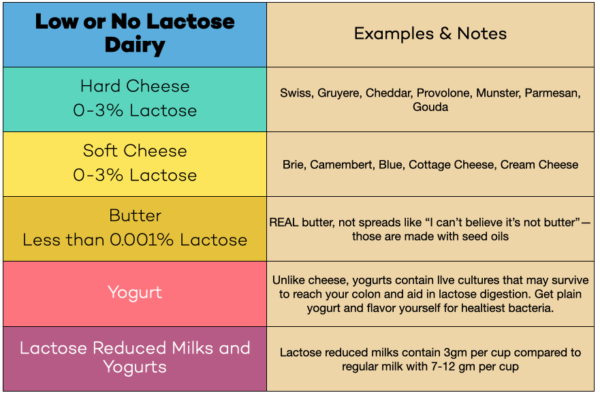

If you are lactose intolerant, you can still enjoy dairy.

Most of the dairy consumed in this country is in the form of butter and cheese. Both of these are naturally low in lactose and most people with lactose intolerance have no problem with cheese or butter. Most hard cheeses and many other low-lactose dairy products are well tolerated by most people who have lactose intolerance. (see chart)

Many people with clinically proven lactose intolerance can easily tolerate 12 grams of lactose or more. Others develop symptoms with less. But usually, it takes at least a few grams. Trace amounts added to things like cookies and other baked goods typically will not cause symptoms.

Your Low-Lactose Dairy Options Chart

What causes lactose intolerance?

Lack of lactase is the cause of lactose intolerance. (Say that ten times fast.)

As mentioned in the previous section lactase is the enzyme that enables us to properly digest lactose sugar. The lactase enzyme lives in cells lining the small intestine, which is the part of the digestive system that starts right after the stomach. Nearly 100 percent of infants are born with plenty of lactase enzymes throughout their small intestinal cells.

As you might imagine, without this enzyme babies would not get proper nutrition and would sadly wither away and die. Lactose intolerance is almost nonexistent until age two or three. At that age, depending on your genetics, you may gradually start to lose the ability to make this enzyme and by adulthood, you may not make any at all. The less lactase enzyme you make, the more likely you will become lactose intolerant. Usually, symptoms do not occur until your lactase enzyme levels fall to 10 percent or less of normal.

Since lactose intolerance is actually the default state, the real question is what causes lactase persistence.

Being able to enjoy milk as an adult is a new evolutionary development.

Some folks have argued that dairy is unhealthy because it’s not natural for humans to drink milk from other species. Evolution, however, would beg to differ.

Think about it this way: Lactose intolerance is actually not a disease. It’s the default state. Lactose tolerance is a new evolutionary development. The fact that evolution went out of its way to change our genes so that we can drink milk into adulthood I think is really cool.

Most mammals lose their ability to make lactase enzymes shortly after weaning when the lactase gene gets switched off. But thanks to genetic variation, between one-third and one-half of the world’s human population has genes that never get switched off. These folks can continue to digest lactose throughout their lives. This is called lactase persistence.

Here’s what we know about the explosive success of this new kind of human. Around 11,000 years ago, people across Africa, Asia, and Europe had successfully domesticated goats, sheep, and cattle. And, according to new genetic research, 10,500 years ago, humans first developed variations of the lactose gene that enabled them to digest lactose for their entire lives. There are now at least 23 variations that keep our lactase genes turned on high. The term for this is “lactase persistence.”

The typical view of evolution as argued by biologists who study lactase persistence suggests this random mutation offered such a huge survival benefit that it spread like wildfire. That might make sense if there were just one mutation. But there are at least 23.

I believe lactase persistence is evidence of an under-appreciated but essential and almost miraculous mechanism of evolution. To learn more about how our genes are able to remember, learn, and make proactive changes to prepare for the future, see Epigenetics and the lactase persistence “gene” below.

Between one-third and one-half of the world’s population has lost 90 percent or more of their lactase enzyme functioning by adulthood, as I mentioned above. The percentage of people with lactose intolerance varies by country. In cold countries like Sweeden and France, 80 percent of adults can digest lactase. While in Ethiopia and India, with warmer climates, as few as 20%. And in regions where dairying was only recently introduced, it’s even lower.

What does temperature have to do with lactose intolerance?

Everything!

Cold temperatures slow microbial growth. Warm temperatures accelerate it. In warm climates, microbial growth starts to alter milk more quickly, reducing the amount of lactose in the dairy products people habitually eat. In cold climates, that process is much slower during much of the year, so more people would be drinking milk that’s basically been refrigerated.

Microbes change our genes by digesting lactose.

Milk is a highly nutritious substance that microbes love almost as much as babies do, so milk attracts microbes and microbes ferment the milk. When the milk is not pasteurized, it seems that the microbes it attracts are not particularly harmful. These microbes gobble up the lactose and at the same time turn the raw milk into yogurt, kefir, byaslag, urum, Filmjölk and hundreds of other fermented drinks as well as thousands of types of cheese.

Where people have traditionally consumed fermented dairy, they got less lactose. Where people have traditionally consumed fresh dairy, they got more. And the amazing thing, in my mind, is how our genes adjusted accordingly.

Your microbiome can help you cure lactose intolerance.

You don’t have to change your genes to be able to drink milk. Research shows that regular consumption of lactose will alter the microbes in your colon in a beneficial way. In other words, when you feed your microbiome lactose, your microbiome gets better at digesting lactose. This short study showed that after just three weeks of lactose exposure, the amount of lactose metabolized by people’s colonic organisms tripled, reducing their symptoms by 50 percent on average.

The dose of lactose people consumed during this trial was quite large, equivalent to between 3 to 8 glasses of milk.

I would expect that you could accelerate the process of curing intolerance, too. If you eat foods containing live lactose-fermenting bacteria. If you want to cure lactose intolerance symptoms and be able to enjoy more dairy, then I would recommend the following foods to fortify your colonic flora to ferment lactose for you:

- Plain whole milk yogurt, Greek or Regular

- Cottage cheese

- Sour cream

- Kefir (chose one with as little added sugar as possible)

Avoiding milk and other lactose-rich foods may bring on lactose intolerance.

If your microbiome can adapt to more lactose to the point it can cure intolerance, as described just above, you’d better believe it will change when you eat less. Think of the microbiome as a collection of neighborhood pets, each with its own dietary requirements. If you put out bird food, you’ll get birds in your yard. If you put out dog and cat food, you’ll get dogs and cats.

There are literally thousands more varieties of microbes in your colonic neighborhood than there are in your real neighborhood, so the variety and types of different foods in your diet can dramatically impact your microbiome. For this reason, it’s very important to be patient and change your diet slowly. This applies to everyone but especially to folks with more sensitive tummies.

Lactose intolerance can begin after a tummy bug.

Many people notice lactose intolerance starting after a bout of infectious diarrhea. In this case, lactose intolerance can be a temporary condition that may resolve in a few weeks, so don’t give up on dairy forever. The temporary intolerance results after intestinal infections damage the cells lining your digestive tract. Within a few weeks, however, the lining regrows and you may very well regain the capacity to digest lactose.

It may also be the case that tummy bugs dramatically alter your colonic flora and need to be rebuilt. If you have developed lactose intolerance recently, you may be easily able to cure intolerance more quickly by eating fermented, live-culture dairy.

Jeremy Lin used dairy to grow taller.

When Jeremy signed on as a Laker, I had the opportunity to ask him about his diet as a child. He told me a really great story about how he was shorter than average as a little boy and did not at all like how taller people patted him on the head. So he asked his mother what he might do to grow taller, and she gave him the perfect answer: milk, protein and calcium. So he maxed out on that strategy and, it appears, his bones maxed out on it too.

He’s not the only one.

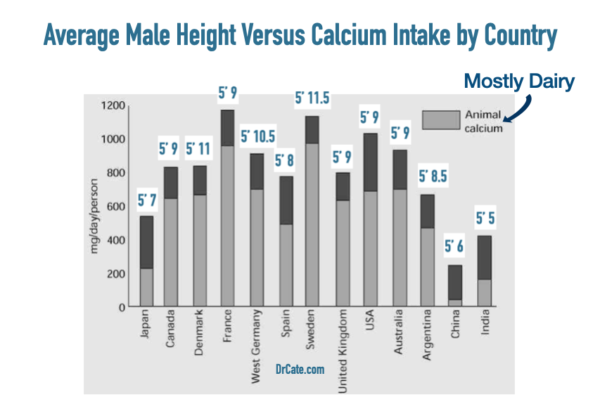

Entire countries grow taller as they consume more dairy.

I’ve made this point before with a graph showing how average height in Japan went down after the emperor banned red meat and up again after the ban was lifted. This is a fundamentally important idea that for some reason makes people upset. The fact is, our DNA depends on the information coming in from our diets in order to regulate our growth and every aspect of our health.

The information your DNA has received by key growth time points in your life can impact whether you wear glasses, whether your teeth come in straight, how tall you will grow, how strong your bones, whether or not your sexual development unfolds normally, and how easily you can reproduce.

So many moms and dads know this intuitively but they are not given the right instructions from the government or their doctors or cookbooks or most nutrition experts. Why not? Because the knowledge we once had was cut off in 1948 by the AHA when they allowed rich and powerful elements of the food industry to take control of the whole nutrition conversation

Epigenetics and the lactase persistence “gene.”

Lactase persistence is made possible thanks to epigenetics.

Lactase persistence is not strictly a genetic mutation. Technically speaking, a gene refers to a part of your genetic code that has instructions for making protein. People with lactose intolerance have normal genes for making lactose and their lactose enzymes are normal. The difference lies in the regulation of the gene that encodes for the lactase enzyme. People with lactose tolerance have new mutations in these regulatory segments of their genetic code responsible for turning on the gene for making the enzyme lactase. The new regulatory segment mutations allow them to keep making lactase their entire lives. Thus, evolution found a way to cure intolerance to milk in adults.

When I looked closely at the timing of these new regulatory mutations I saw something incredible. First, lactase persistence seems to have developed immediately after domesticating dairy animals, having been found in bones as old as 10,500 years BCE. And it appears that different mutations conferring lactase persistence developed in at least 23 different populations around the world, many arising at almost the same time.

Your DNA is smarter than you think

Lactose tolerance developed faster than the standard model of evolution can explain

Lactose tolerance developed in the blink of evolutionary time. This suggests to me that there’s more to evolution than the standard model of evolution can explain.

The standard model relies on random mutation and natural selection to drive genetic changes. It’s extremely improbable that lactase persistence in all these different groups was a result of random genetic mutation. Epigenetics likely stepped in to inform the process of genetic change. As I explain in my first book, Deep Nutrition, epigenetics provides a mechanism for our genes to respond to changes in our environment. This mechanism is evidence of a kind of intelligence–memory and language–built into the miraculous molecule we call DNA.

In support of my non-random mutation hypothesis, the authors of this article show that many people continue producing lactase without any of the known mutations thanks to epigenetic methylation changes. I find that fascinating because it suggests that before making any permanent mutations, DNA experiments with temporary changes to make sure that they’re going to be beneficial.

Others have made similar speculations about the interplay of genetics and epigenetics in non-randomly guiding DNA changes over time. In light of the intelligence of this system, I think we need to drop the term “mutation” for a more respectful descriptive term.

I heard dairy causes osteoporosis. Why do you recommend it?

Dairy does not cause osteoporosis. This often-repeated claim is not supported by credible research, and, truly, it is entirely illogical to suggest such a thing.

Folks who make this claim will try to sell you some line about how dairy is alkalinizing or makes your bones ‘brittle.’ But these claims defy common sense–nature created milk to support bone growth, not to give babies osteoporosis, and milk contains numerous bone-supporting nutrients. Whenever a claim defies common sense, it’s an extraordinary claim. Any extraordinary claim really needs to be backed up with an extraordinary abundance of research. When I look at the studies they use to support these claims, it does not meet that burden.

The pseudo-science against dairy.

Let me give you an example.

This article from the Cleveland Clinic puts a terrifically negative spin on dairy. There is no research to support the title claim, that milk makes bones brittle. When you look up the citation for the claim that people who drank more milk had higher mortality rates and more fractures, the article itself says the association only existed in a subgroup of people in the study. Becuase of that you cannot generalize the results to larger populations, and the authors try to caution against doing exactly that.

Nor is there support for the dietitian’s warning to limit milk drinking to one glass per day. And there is no research supporting the claim that dairy contains “other substances that may warrant some moderation”–whatever that means.

Why do I bring it up? Because there is a large anti-dairy camp that calls milk inflammatory, diabetes promoting, and yes, has even made the claim that the most bone-health supporting substance on the planet is bad for your bones. These folks come out of the woodwork from time to time and when I do the legwork to look up their affiliations I find they’re supported by processed food money.

Indeed, when I look up the author of the Cleveland Clinic study linked above, I find she was listed as the president of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, a branch of the American Dietetic Association. The ADA notoriously gets millions of dollars from companies selling soda and dairy alternatives. They are a problem because I have had the unhappy experience of meeting patients who have taken this misguided, conflicted advice at face value and suffered life-changing fragility fractures.

Why do some people develop allergies to food proteins?

If you are allergic to the protein in cow’s milk, you probably developed the allergy-inducing antibody due not to any defect in your genetics, but due to a defect in the nutrition guidelines. Our current guidelines utterly fail to properly describe a healthy diet.

Cow’s milk protein is often included in processed foods, and the ingredients in processed food include inflammation-promoting seed oils and microbiome-disrupting sugars. This one-two punch disrupts your immune system as I describe in this article.

If you are allergic to cow’s milk, you may be able to drink goat’s milk. Different animals have different proteins. As do cheeses that have been aged for 90 days or more.

Do you need dairy in your diet if you don’t like it?

Of course not. If you don’t like dairy you have to have any. The point of this article is not to tell you that you must consume dairy to cure intolerance. It’s just to help you if you have been pining for cheese, yogurt, butter, or any of the other low-lactose dairy products. If you are confident your symptoms are lactose intolerance and not something more serious, then you can safely experiment and hopefully will find a way to continue participating in the ancient human ritual celebrating the wonderful gift of the ungulate.

Further reading:

- Lactose Intolerance and Bone Health: The Challenge of Ensuring Adequate Calcium Intake (2019)

- Genetics of Lactose Intolerance: An Updated Review and Online Interactive World Maps of Phenotype and Genotype Frequencies (2020)

- Update on lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management (2019)

This Post Has 5 Comments

Note: Please do not share personal information with a medical question in our comment section. Comments containing this content will be deleted due to HIPAA regulations.

Hi! I am currently reading your book Deep Nutrition and have The Fatburn Fix on my to be read list! 🙂 Your article gives me hope as I feel like I came down with what I think is lactose intolerance very suddenly a couple years ago and it’s been so frustrating. Though after reading this article I’m not sure if I have lactose intolerance or something more serious. Are wheezing, skin rash, and joint pain the only signs of a dairy allergy or something severe like it?

Hello, Dr. Kate! thank you very much for tons of valuable information, I got acquainted with your book “Deep Nutrition” (if you are interested, in Russia it is called “smart gene, what kind of food your DNA needs”) in 2019, and since then it has become something of a bible in my kitchen. I am very interested, what do you think about A2/A22 milk? we moved to America not so long ago, and the only milk with a normal taste was milk from cows with A2/A2. I don’t have a milk intolerance, but I’m afraid this kind of milk can cause problems. In Russia, where I come from, I always drank the milk of village cows

Hi Ksenia, and Welcome!

How lucky that your village had cows. I hope folks over there are able to continue that way of life!

Milk that is not A2/A2 is perfectly fine. There’s a bit of confusion about it due to the failure to distinguish correlation from causation. I actually do discuss that in the English version on page 393. Sometimes the translations cut out a lot of materials so I’m curious if your version has a section called Frequently Asked Questions?

Sorry this question is not related to this post but I can’t seem to find a straight answer elsewhere online. Is cold pressed extra virgin rapeseed oil something you would suggest to avoid like the other hateful 8 oils?

Good question.Rapeseed is also known as Canola, which is how I refer to it throughout the website if you want more info. Canola has a lot of PUFA and should not be heated or it oxidizes and toxins form. Most of us get too much PUFA, so even if you don’t cook with it, it can contribute to oxidative stress and promote additional oxidation reactions in your body’s tissues.