Low Smoke Point Olive Oil on High Heat–Is It Safe?

Table of Contents

- Olive Oil has a Low Smoke Point. Can you still cook with it?

- Invisible Oxidation Makes Oils Toxic BEFORE They Start to Smoke

- Virgin Olive Oil Has A Lower Smoke Point Than Refined Olive Oils–And It’s Healthier

- Can You Use Olive Oil For Deep Fat Frying?

- Can I use virgin olive oil to char my steak?

- Stick with BROWNING For Great Flavor Without Toxicity

Olive Oil has a Low Smoke Point. Can you still cook with it?

We’ve all heard a thousand times high smoke point oils like soy and canola are the oils of choice for cooking–especially high-heat cooking. This is a particular concern for professional chefs who typically cook with temperatures far higher than those used by a home cook.

If the oils aren’t smoking that must mean, the thinking goes, that they are chemically stable. No smoke, no free radicals, no toxins. No problems.

But I want you to set aside, for a moment, everything you’ve been told about smoke point and its significance in communicating to you whether or not you are chemically punishing the cooking oil in your pan. What matters is something you can’t see.

Invisible Oxidation Makes Oils Toxic BEFORE They Start to Smoke

Believe it or not, as a general principle, the lower smoke-point cooking oils are a far better choice for any cooking application, at any heat, than the highly refined oils with a higher smoke point.

Refining Raises Smoke Point

I’ve written extensively about the unique toxicity of eight refined vegetable seed oils I call the Hateful Eight. The heat and pressure required to efficiently extract these oils yields a crude oil that’s foul-smelling, caustic, and inedible. Cleaning up the caustic compounds in the crude requires extensive refining, including degumming, dewaxing, washing out any solvents used, deodorizing, and bleaching. This removes most of the harmful compounds.

It also strips away the antioxidants (more on that in a moment) and the free fatty acids.

Free fatty acids ignite at lower temperatures than the triglycerides that constitute the bulk of the oil. Removing those free fatty acids raises the smoke point. That’s the whole reason refined oils have higher smoke points than their unrefined counterparts.

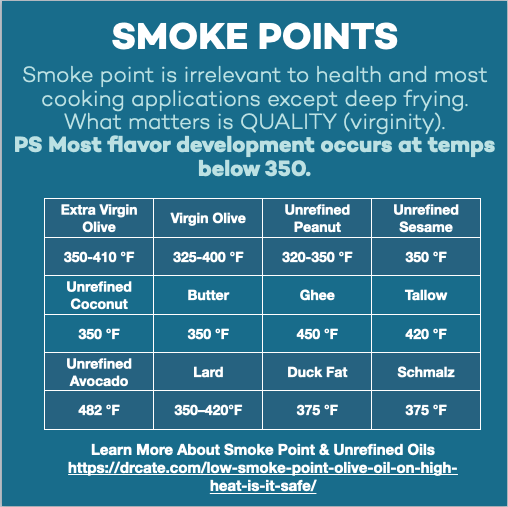

Olive oil smoke point, by grade.

Let’s take a look at the three grades of olive oil to see how free fatty acid content (based on oil weight) affects the smoke point.

- Extra virgin olive oil: Free fatty acids less than 0.8%; smoke point 350-410 °F.

- Virgin olive oil: Free fatty acids between 0.8% and 2.0%; smoke point 325 and 400 °F.

- Refined olive oil: Free fatty acids 0.05%; smoke point 390–470°F (199–243°C).

Virgin olive oils are divided into two quality grades, extra virgin, and regular virgin, based on their free fatty acid content. When it comes to virgin oils (virgin meaning unrefined), lower free fatty acids indicate better quality. Fresher fruit and gentler handling keep the free fatty acids locked in triglycerides. Rougher handling activates enzymes that release more free fatty acids.

Refining virtually eliminates free fatty acids. It produces a clear, odorless, virtually flavorless, all-purpose cooking oil that can take the heat without smoking, at least until they are subjected to extreme temperatures.

How great is that? No smoke, no toxins. Or so they tell us.

But they’re wrong. That notion, sold to us by the industrial oil industry, is a lot of smoke and mirrors.

Removing Antioxidants Exposes Polyunsaturates to Toxin-Generating Oxygen Reactions

As I mentioned, a bycatch of the refining process is stripping away the antioxidants. This is key, because antioxidants stand guard, defending fragile fatty acids from oxygen, just as they do in vegetables and plants and every cell of your body. Without antioxidants, the easily oxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acids are left vulnerable to oxidation.

The invisible oxidation–oxidation that doesn’t produce smoke–breaks the bigger fatty acids that our bodies can use into smaller pieces that our bodies can’t. These smaller pieces are called lipid oxidation products (LOPs), and many have serious toxicity. One of the worst LOP categories is the alpha beta-unsaturated aldehydes. Dr. Martin Grootveld has been studying LOPs in frying oils and fried foods for decades. He’s published many papers on the subject including one that warns a single serving of fast food French fries contains the equivalent toxicity of smoking a pack of cigarettes.

Where do toxins in refined oils come from?

As the oils leave the factory, sans antioxidants, they contain between 0.6% and 5.2% LOPs. [Here’s a citation for organic canola oil, the numbers are similar for other members of the hateful eight]. These LOP contaminants act as catalysts that accelerate oxygen attacks on the polyunsaturated fats in the refined oils.

I’ve compared these LOPs to zombies because when one of them touches a polyunsaturated fatty acid, it becomes a LOP, which can then also generate LOPs. The zombie effect explains how just a little bit of LOP becomes a big problem. In the setting of nearly zero antioxidants, plus heat and oxygen, that zombie action can transform what would otherwise be a relatively healthy meal into one that creates an invisible circus act of pro-inflammatory monster molecules.

Virgin Olive Oil Has A Lower Smoke Point Than Refined Olive Oils–And It’s Healthier

When we stop focusing on smoke point, we’re allowed to ask the crucial question regarding the healthfulness of various cooking oils: “If smoke point isn’t the best way to judge which cooking oils we should use at whatever temperature, then what are the earmarks of a healthy cooking oil?

The simple answer is quality.

If you were to say that, in a sense, seed oils hide behind food experts’ infatuation with smoke point, you’d be right.

As I detail in my latest book Dark Calories, it’s time to look past the smoke and think biochemistry.

What’s the very opposite of a refined oil? Unrefined. What we might call “a living oil.” Oils that have not been stripped of basically everything except the triglycerides. They still contain protective antioxidants and other nutrients. They also still contain free fatty acids, which are the molecular components that start smoking even at moderate temperatures.

This applies to all unrefined oils, including the star of this article and something you probably have in your kitchen: olive oil—a far better choice than any member of the Hateful Eight.

Any unrefined oil is far better than its refined counterparts. Not just for cooking, but for everything. For frying, go for unrefined olive oil or any of my recommended oils if you can afford it.

The one exception to the rule is in a deep-fat fryer.

Can You Use Olive Oil For Deep Fat Frying?

For deep fat frying in a pan, you can use any oil with a smoke point of roughly 350 degrees or greater. Most foods will develop that beautiful golden brown color between 290-330 °F. So 350 °F gives you a little wiggle room to speed things up. Please be very careful when frying in a pan. If you exceed the smoke point it will boil over the pan. This is true for any oil.

That’s basically why deep fryers were invented.

The deep fryer makes deep frying safer because you can set the temperature precisely, unlike a pan on the stovetop. In fact, deep fryers revolutionized restaurants because suddenly you didn’t need a chef to produce a consistent product. That’s why so many restaurants now offer multiple deep fryer-cooked options. Many restaurants are secretly deep frying foods you wouldn’t expect, like eggplant parmesan for example. They do this because it’s faster and that keeps the price down.

Back in the day, McDonalds used tallow in their deep fryers. At one point, their carefully guarded secret frying oil formula also included sesame oil. I’m old enough to remember those fries and let me tell you they were the stuff of happy childhood memories. Even though I’d eat so many that, at least once, I threw up afterward. Those fries were less toxic than today’s, but probably not nontoxic.

Any frying oil can become toxic–if reused too many times.

These days the fries are terribly toxic and less tasty.

For frying at home, you’ll get the best results with tallow. Tallow’s more saturated fatty acids resist oxidative degradation. They also stay more on the surface of whatever you’re frying, so the food doesn’t get soggy with oil. This is probably what Julia Child noticed, and disliked, about the switch to what she called “the nutritionists’ oils.”

Watch Julia Child seriously disrespecting seed oils in this YouTube clip.

Can I use virgin olive oil to char my steak?

Sure you can. But I wouldn’t recommend it. Not because of the oil, which will still yield less toxicity than a high smoke point oil. Because of what charring does to steak.

Charred food is part of our eating experience. A massive tomahawk steak served up at a high-end Manhattan steak house in just minutes with a perfect char on the outside and a medium rare center. That burnt potato chip you shyly admit you kind of like. Or that Vietnamese pho takeout, which typically involved slightly scorched/blackened sliced onions and star anise.

Did you ever toast marshmallows over a campfire and accidentally set it on fire, while the person next to you had the good sense to hold the marshmallow a few inches further from the fire and got a nice, golden-browned marshmallow that wasn’t jacketed with a black, bitter crust? There’s a lesson there.

Charring Food Also Generates Toxicity

I have no intentions of categorically condemning a little char here and there. I mean only to suggest that you might want to be a bit cautious with charring your food, even when using the right cooking oils or fats, as charred food itself has been shown to produce heterocyclic aromatic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These compounds start forming above boiling point, but they don’t form rapidly until about 392 degrees F (200 C). They can stress the liver as it struggles to break them down with detoxification enzymes and have been associated with any number of cancers.

The existence of 1500-degree grilles, and the like, has taught me that men are encouraged to use a flaming hot cooking implement imbued with danger, lest their Y chromosome sprout a second leg and become an X (…that’s biology humor). But I’m not sure extreme heat is the best way to make tasty food. I say this because, when it comes to cooking up complex, savory, roll-your-eyes-back flavors, charring kinda goes a bit far over the edge.

Cool those engines a bit and learn to brown your food.

Stick with BROWNING For Great Flavor Without Toxicity

The whole point of cooking with higher heat is getting what many would consider a more desirable flavor, aroma, and color. As you’ll see, these reactions occur at temperatures well below the smoke point of quality olive oils.

Maillard Reactions: Delicious Chemistry from Protein and Sugar

One of two main reactions responsible for these desirable traits is the Maillard reaction, which is the chemical term for browning, also known as searing. It refers to reactions between proteins and sugars that tend to create savory flavors, and impart a brown color. They generally develop between 250 and 330 °F. The flavorful compounds include furanones (sweet and caramel), pyrazines (savory, nutty, and roasted), and thiophenes (meaty). Browning can also give any meat a crispy exterior. If you sear meat before stewing it, the flavor slowly incorporates into the cooking liquid, creating a deeper, more complex flavor.

These Maillard browning reactions do destroy some of the nutritional value of a food. However, the end products of Maillard reactions are not considered toxic.

Caramelization Reactions: Delicious Chemistry from Sugar

Caramelization, or the browning of sugar, turns ordinary vegetables like onions into little gemules of flavor. Caramelization is different from Maillard reactions that occur between proteins and sugar. It’s a kind of pyrolysis, meaning burning, which we usually think of as bad. But caramelization doesn’t ruin your food. In fact, it has the opposite effect, creating some of the most tantalizing flavors imaginable. Like, for example, caramel. Also sweet, butterscotch, nutty, toasty, bitter, and creamy. These compounds are also nontoxic.

Caramelization typically occurs between 320°F (160°C) and 360°F (182°C). The exact temperature depends on the type of sugar (and other factors):

- Fructose: Found in fruits, vegetables, and honey. Fructose caramelizes at a lower temperature of around 230°F (105°C)

- Galactose: Found in milk. Caramelizes at 320°F (160°C)

- Glucose: Found in milk, fruits, rice, and many other foods. It’s the most common sugar on Earth. Caramelizes at 302°F (150°C)

- Sucrose: Also known as ordinary sugar. Sucrose caramelizes at around 320°F (170°C)

- Maltose: Found in fruits, honey, molasses, sweet potatoes, and sprouted barley. Caramelizes at 360°F (180°C)

If you master browning, your guests won’t be frowning. If you’ve got a lot of char, then you’ve likely gone too far.

The Takeaway

Forget smoke point. Use virgin oils. Stay clear of the Hateful Eight. If you have to use a refined oil, go for one of the refined oils on my OK but Not Great list here. Use low or moderate heat instead of intensively high heat (unless doing stir fry, in which case you’ll be protecting the food and oil by frenetic tossing and a short cooking time).

And, of course, read Dark Calories, so that you can understand all of this stuff to a level that you can be confident about habits, whether cooking for yourself or eating out.

Final thought: if you happen to find yourself trying to rekindle that childhood camping memory and put your marshmallow too close to the fire and accidentally char it, just pull it off the stick, grab another marshmallow from the bag, and try again. It’s ok to screw it up. You learn. You try to do better next time. Just like a chef would do.

Please note: Please do not share personal medical information in a comment on our posts. It will be deleted due to HIPAA regulations.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Note: Please do not share personal information with a medical question in our comment section. Comments containing this content will be deleted due to HIPAA regulations.

I’m really appreciate the advice on cooking with heat.. I was already getting tired of recipes calling for medium high heat at the beginning of a recipe thus not being able to turn your back on the stove for a second.

Have read your books and I am now reading Dark Calories and really appreciate the information. My favorite quote of yours from Deep Nutition…” I know I had you at butter”” Is true in spades And now I’ve found Irish Butter! It’s truly marvelous. Good on ya Lass.

Please comment on the adulteration of olive oil. I suspect most of the oil sold as evoo is blended with seed oils. I have been buying CA Ranch Olive Oil made with CA olives as it seems to be a reliable brand. But who knows. Home to know if the olive oil is all evoo?

This deserves its own post and I’ll be doing that with a goal of answering y our question on how to tell if its adulterated. Stay tuned (be sure to subscribe to my newsletter ASAP so you don’t miss it)