Synthetic meat producers claim nutritional, ethical, and environmental benefits. The media often repeats the claims. Are they misleading us?

Why doesn’t meat taste like it used to?

Table of Contents

- Warning: Learning why meat tastes less flavorful than when we were kids may trigger thoughts of going vegan.

- What is PSE meat?

- What causes PSE and DFD meat?

- Random Genetic Mutations?

- Human-Induced Genetic Mutations

- Fixing the Problems—Sort of

- Porcine Stress Syndrome

- Is Porcine Stress Syndrome Under-Diagnosed?

- How Common is PSE in Chicken?

- Why Meat Tastes Different than It Used To

- What About Pasture-Raised Birds?

- How Did We Get Here?

- Why this matters.

- PSE & Mutant Meat Stats

- What Happened When One Farmer Did Everything Right?

- The Actionables

- Further Reading

Warning: Learning why meat tastes less flavorful than when we were kids may trigger thoughts of going vegan.

Meat tastes good. But not as good as it used to.

I wasn’t actually planning to tackle the depressing topic of increasingly bland chicken and pork. But while looking to round out my shopping list of healthy, seed-oil-free foods, I ran into these carnitas. Carnitas are a traditional Mexican pork dish, and this product was made with the traditional lard, instead of vegetable oil. It looked like a potential time-saving shortcut that I wanted to recommend. But first, I needed to know about a few of their ingredients: Sodium Acetate, Sodium Carbonate, and Sodium Citrate.

When trying to answer the question Why is sodium carbonate added to meat? I came across a disturbing explanation. Apparently, sodium carbonate (NaHCO3) “can improve the palatability and process-ability of PSE (Pale, Soft, Exudative) meat, sow loins, and PSE-like chicken breast.“

This article is continued below...(scroll down)

I couldn’t go any further without finding out the answer to these two questions: What on Earth is pale soft exudative meat? What is PSE-like chicken breast?

Investigating the meaning of those terms took me deep down a feather-lined rabbit hole. It leads to a little-known, present, and growing problem emerging from modern farming practices.

What is PSE meat?

PSE stands for pale, soft, and exudative. PSE meat is paler than normal, softer than normal, and moist thanks to an exudate that oozes from the flesh. (It’s also slimy.) It was first noticed developing in pork in the 1960s, and then in chickens in the 1990s. [Coping with the PSE syndrome in poultry meat ]

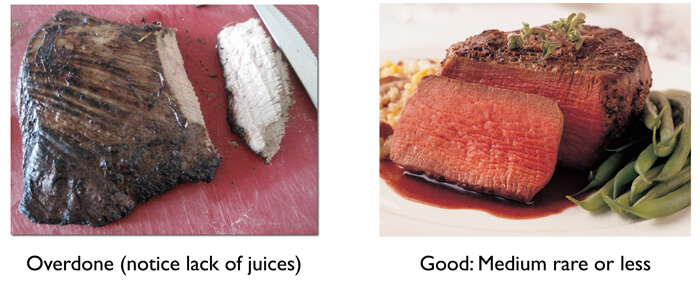

The issue affects the most high-value cuts, chicken breast, pork hams, and tenderloins. The result is a chewy, dry meat, that tastes significantly blander than its non-PSE counterparts.

The meats affected by PSE fetch much lower prices, since their problems must be disguised. Instead of pricey chops, hams, and fillets, they may end up in the discount bin of so-called structured meat products like nuggets, crispy chicken tenders, and fake baby back ribs. That’s only if they fail the inspection, though. Some are sold as is, since most consumers don’t know the difference. As off-putting as it is, it’s supposedly not horrible for our health, as long as you cook it thoroughly.

As if PSE wasn’t enough, farmers also deal with another condition called DFD, for dark, firm and dry. Even though the condition sounds like the opposite of PSE, it causes similar taste and textural problems.

The next mystery was why. What I found made me madder than a wet hen. After you read this article, I’d love to hear in the comments what you think of the whole, cockamamie story.

What causes PSE and DFD meat?

There is more information on PSE than DFD, and it appears PSE is more of a problem in chickens and pigs, while DFD is more of an issue in beef cattle. So I’m going to focus on PSE mainly.

When the PSE problem first popped up, in the 1980s, ag scientists and veterinarians quickly deduced that a certain type of acid called lactic acid could cause the problem.

Lactic acid is a normal byproduct of muscle anaerobic metabolism. Anaerobic means without oxygen. When muscles work too hard, they can outstrip their oxygen supply. When that happens, a byproduct of glucose metabolism called lactic acid starts building up inside the cell. Lactic acid makes us “feel the burn” when we’re exercising to the point of exhaustion.

Too much lactic acid lowers the pH within muscle cells. This metabolic problem can actually become so severe that the muscle proteins start denaturing and the cell structure begins breaking down.

I’m not a veterinarian, so I started thinking about similar processes in humans. This issue actually sounds to me very much like something that can occur in humans, called rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis means literally rapid muscle breakdown, in Latin. It can be brought on by drugs, hyperthermia, dehydration, and extreme exercise. Rhabdomyolysis is a medical emergency, and complications are potentially fatal if not treated quickly.

But pork and chicken spend their lives indoors in climate-controlled indoor cages, so why would they develop this issue?

Random Genetic Mutations?

After the PSE problem was first observed in pigs, veterinarians recognized that it was related to a human condition called neuroleptic malignant syndrome, or NMS. NMS is characterized by mental status changes, muscle rigidity, fever, extremely high blood pressure, and rapid heart rate. It can be fatal within minutes to hours.

NMS develops in people exposed to an anesthetic called Halothane, if they have a specific gene that changes how they metabolize the drug. Antidepressants that affect serotonin levels, like Prozac and Paxil, can cause the issue in genetically susceptible people, too. Veterinarians soon discovered a similar mutation had developed within various breeds of hogs. (As far as I can tell, the issue has not been compared to rhabdomyolysis. I bring this up because NMS also happens to be one of the conditions that can bring on rhabdomyolysis.)

Given the genetic underpinnings, the solution to PSE seemed clear. Hog breeders started testing for the gene, and were able to quickly breed out the problem. That helped, but it didn’t go away entirely. Nor did it explain why the problem also affected turkeys and chickens.

So, the random gene mutation idea doesn’t feel like the whole story. After all, what are the chances that so many different breeds of different animals would suddenly develop similar random genetic mutations?

Human-Induced Genetic Mutations

In search of a more complete explanation for the PSE meat problem, I talked to Norman G. Marriott, an Emeritus Professor of Food Science and Technology at Virginia Tech. He suggests the problem is more systemic than just a single gene mutation. It’s related to generations of selective breeding, and specifically the recent selection of animals that build very little fat.

His perspective on the problem goes all the way back to WWII, with breeding for higher fat animals, interestingly enough. He explained that the glycerol in pig fat was key to the war effort because chemists combined the glycerol with nitrogen to make the nitroglycerine used for explosives. After the war was over, we no longer needed all that glycerol and started raising pigs for meat again. When the fat phobia of the 1970s and 80s started, we flipped the genetic preferences in the opposite direction, looking for leaner and leaner animals. In Dr. Marriot’s view, the PSE meat problem began after we took that meat-building, fat-minimizing trend a bit too far.

Dr. Marriot writes, in this article, that “The production of leaner pork has often been accompanied by lower quality muscle.” As the article says, by selecting animals that build very little fat, we’ve changed how their muscles work. We’ve forced them to metabolize a limited supply of glycogen for energy, rather than fat. Fat is normally the primary cellular fuel in all mammals. It seems that one consequence of selecting for leanness has been a relative inability to metabolize fat. This makes the animals dangerously susceptible to stress because stress accelerates the already genetically accelerated glycogen metabolism to the point that lactic acid levels exceed tissue tolerances.

It’s like the muscles are being marinated alive. When muscle cells break down, this breaks apart some of the muscle myoglobin that gives meat its red color, making the meat pale. This also makes the meat lose its integrity, creating an abnormally soft texture. And the fluids leaking from the cells collect to form the slimy exudate.

Fixing the Problems—Sort of

According to Dr. Chad Carr, a meat scientist at the University of Florida that I spoke with, the PSE issue is now largely solved. At least as far as US pork goes.

Once pig breeders discovered the excessive lean-meat issue, they went to work selecting for slightly higher fat content. Veterinarians also recommended some (long-overdue) common sense changes to porcine slaughtering practices that reduced the associated stress. They kept the animals in social groups and euthanized them with carbon dioxide rather than electrocuting them with a jolt that often caused seizures. Seizures cause muscle spasms and accelerate acid formation in these glycogen-dependent animals.

As a result, the rates of PSE pork have come down from their high of 40 percent to much lower, perhaps as less than 5 percent (more details forthcoming, see correction below).

Dr. Carr told me that lactic acid overproduction only occurs around the time pigs are harvested, and only when they are both stressed and killed by electrocution. However, according to another expert, the animals may be susceptible to these metabolic problems whenever they are severely stressed.

Porcine Stress Syndrome

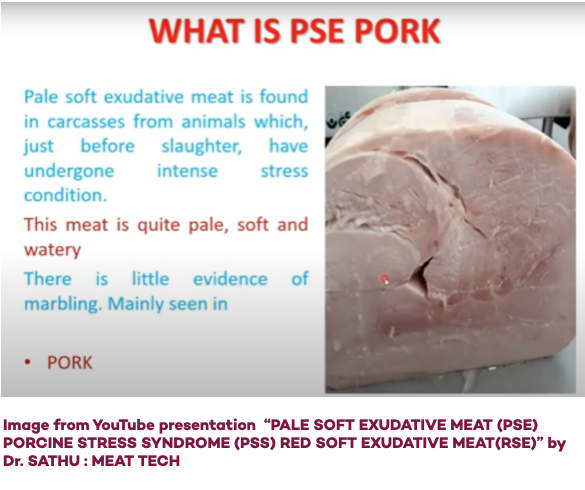

The above image is from a video posted here by Dr. Sathu T, Assistant Professor, Department of Livestock Products Technology & Meat Technology Unit, Kerala Veterinary & Animal Sciences University. Dr. Sathu says there is another name for PSE, that is PSS, or porcine stress syndrome.

While you can only identify PSE after the pig is killed, you can identify PSS while the animal is still alive. A short list of behavioral changes indicate that a little piggie might be in the midst of having its muscles start to break down in ways that lead to PSE meat. Signs include irregular breathing, reddening of the skin, hyperthermia, tail and muscle tremors, inability to walk, and collapse and usually die within minutes. Later in the video, Dr Sathu explains this can be brought on by any sort of maltreatment that stresses the animal, and prevented by gentle treatment.

According to Dr. Sathu, a variety of conditions cause PSS, not just being electrocuted. He lists out various mistreatments people should avoid. These include kicking, yelling, screaming at the animals, depriving them of water, and light, and removing them from their social groups. This may be especially important before slaughter because it’s an especially stressful time.

PSS and PSE may be more of an issue in India than in the US because the weather in most of India tends to be much warmer than in most of the US. (Also, many of the country’s religions make the population at large mindful of animal welfare.)

Even Dr. Carr admits that the rate of PSE may be closer to 15 percent than 5, which is pretty significant. And my guess is that if we don’t address the root of the problem the way they do elsewhere, it is going to keep getting worse.

Is Porcine Stress Syndrome Under-Diagnosed?

It seems to me that PSE and PSS would not just be limited to this small slice of the animals’ lives. This seems like the kind of thing that may happen at any point. Roughly 15 percent of pigs die before reaching maturity, and about 30 percent of that total mortality is unexplained by other causes. This condition could certainly contribute to that unexplained 30 percent, and to increased susceptibility to infection, bleeding ulcers, and the other known causes.

How Common is PSE in Chicken?

I was unable to find much about this for the USA. In Brazil and Sri Lanka it appears to occur as often as 40 and 60 percent, respectively.

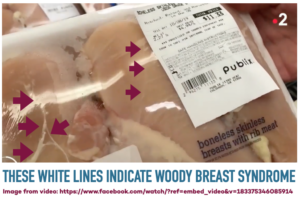

The problem discussed most often among commercial poultry breeders is slightly different in the US. It is called woody breast syndrome. This condition occurs when fibrous connective tissue replaces muscle, making the meat extra hard to chew, and “woody” textured. This also causes further textural changes sometimes called “spaghetti meat,” as shown in the image, below.

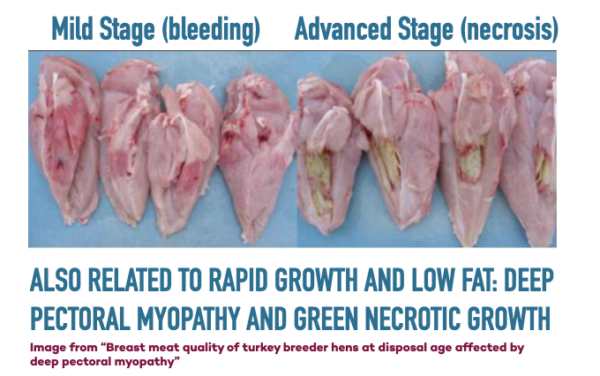

In some cases, large portions of muscle actually die, and the animals’ body reabsorbs the necrotic tissue, leaving a green residue behind.

This set of problems reminds me of compartment syndrome in humans. This serious condition is caused by high pressure within the muscle that reduces blood flow. It needs urgent treatment with something called a fasciotomy to prevent the muscle from dying. Fasciotomy involves surgically flaying the fibrous tissue surrounding the muscle to reduce the pressure in the affected muscle compartments. With the pressure relived, blood flow returns, preventing tissue necrosis (death).

Why Meat Tastes Different than It Used To

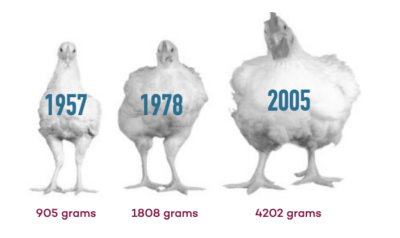

I remember when chicken tasted like chicken. Now it tastes like nothing at all. Until I learned about PSE syndrome, I figured the animals’ rapid rate of growth basically diluted the flavor. In case you haven’t heard about this already, 60 years ago, it took chickens 16 weeks to reach 3 pounds. Chicken now reach 4 or 5 pounds in just 6 to 7 weeks.

These changes do more than just make meat grow fast. They profoundly change the muscle.

Fast-growth muscles share two highly abnormal traits. First, they develop in spite of the fact that the animals rarely move. And second, they seem to not produce energy from fat at all. As a result, they “run out of steam” in minutes.

A local FL farmer made me wonder if these animals aren’t altering their behavior to adapt to their unnatural physiology. He told me he raises two breeds, the newer fast-growing chickens and also a heritage breed. He’s noticed such a huge difference between the breeds in terms of their activity that, he says, it’s like they’re like completely different species.

The fast growers, a breed called Cornish Cross, stand up for a few seconds, take a few pecks of grain, and sit down. They don’t take too much advantage of all the fresh, green pasture he provides. On the other hand, the minute he lets the heritage breeds out for the day, they’re on the go, and they stay active all day long; socializing, exploring the fence lines, and pecking around for seeds and bugs.

This independent foraging behavior is one of the main benefits of putting birds on pasture. The birds get more nutrition so their meat is more nutritious–and more flavorful.

What About Pasture-Raised Birds?

The farmers who I spoke to who raise the fast-growing cornish cross on pasture all reported to me that they have not had any PSE, woody breast, or other growth anomalies to deal with. They also report near-zero mortality rates. This is much better than neighboring farmers growing chickens indoors purely on grains, who reportedly carry out at least three or four dead birds on a daily basis.

Learning about these acid-muscle problems has made me wonder if these birds are not just dying of infections, as we often hear, due to their unhealthy, cooped-up growing situations. Complications from muscle necrosis and rhabdomyolysis may also be a contributing factor.

How Did We Get Here?

Many have pointed out that our flavorless, unhealthy food chain is a natural outgrowth of needing to produce more food more “efficiently” to serve the needs of our growing population. That is only part of it.

In my view, this also emerges from fat phobia. Which, in turn, stems largely from cholesterol phobia. Without these phobias, we never would have selected ultra-lean animals. By doing so, we have now pushed porcine and poultry biology to the point where their muscles start disintegrating while they’re still alive.

Why this matters.

For one thing, mutant meat is less nutritious. The muscle barely functions, and is undoubtedly lower in antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals. The flavor didn’t used to come from added chemicals. It came from nutrients. When our food is flavorless, this is an important warning that it’s less nutritious.

Secondly, when our ingredients are lower quality, our meals will be less flavorful. When our home-cooked meals don’t taste as good as drive-through dinners, we’re going to end up eating more drive-throughs. And that often means more oxidized vegetable oil and other processed junk.

Another reason this issue matters, at least to me, is the humanity of it all.

I heard decades ago that pre-slaughter stress was not good for the animal and that could change how the meat tasted, but I mistakenly got the impression that it was a metaphysical issue. That was my own ignorance. But I must say, everything I’d previously heard about pre-slaughter stress utterly failed to capture the reality of PSS and PSE.

If you haven’t already checked out the video mentioned above, please take a minute to watch the video clip of this stressed PSS-affected animal at 6 mins.

That’s not “I don’t like this” stress. That’s “I’m about to die” stress.

Of course, vegans have capitalized on this and no doubt turned many off meat altogether.

So why am I writing about this? Definitely not to make you feel bad for enjoying meat. This gross injustice to animal welfare is not something that we did just out of sheer ignorance or bad luck. This is in large part thanks to the cholesterol phobia, the American Heart Association (AHA), and the fact that the processed food industry has been funding much of the AHA’s nutrition research (which you already know if you’ve read my articles here).

PSE & Mutant Meat Stats

- How many pigs eaten across the world? 1.3 billion

- How common is PSE in pork? In 1999, it was as high as 60 percent. I could not find a more recent answer possibly related to the assumption in the USA at least that the problem has been solved.

- How many chickens? 74 billion.

How common is PSE in poultry? I could not find a US report but in Canada it’s between 7 and 43 percent, 70 percent in Sri Lanka,

What Happened When One Farmer Did Everything Right?

One of my favorite farms is Primal Pastures, which has also spun off another company called Pasture Bird. I love these guys because they try to do everything right, from the ground up. Their birds get access to new, fresh pastures on a daily basis.

In doing the research for this article I spoke to one of the founding partners, Farmer Robb, about the company’s experience with PSE. It turns out, they never had a problem with it. But I was saddened to hear that it was not for the reasons I thought. I thought they were raising heritage birds and one point they were. Unfortuntely, they got so many requests for more breast meat and complaints about the flavorful (not bland) dark meat that they had to give that up.

Until there is more consumer demand for flavorful meat, some farmers feel they have no choice but to raise the standard, faster-growing Cornish Cross. Fortunately, raising these birds on pasture seems to prevent the various mutant meat problems.

A likely reason is that they are willing to tolerate a “lower feed efficiency.”

Feed efficiency refers to the portion of calories fed that get converted into animal, rather than being burned off. Being outdoors and moved, they are more active and burn more calories than conventional chicken. As a result, all pasture-raised birds take a bit longer to grow than the typical chickens kept indoors. A slower growth rate seems to help prevent the terrible and likely painful problem of breast tissue outgrowing its own blood supply.

The Actionables

This has probably been a pretty depressing article to read and I hope I didn’t ruin your dinner. If you made it all the way to the end, I want to leave you with a positive thought. This gives us more reasons to seek out farmers who grow animals on pasture, particularly the farmers who grow heritage-breed chickens and pork. And if you are a white meat person, maybe consider giving dark meat another try.

Also on a positive note, some people are working to make finding heritage chickens easier for us. Heritage Poultry Conservancy is one such organization. And if you know of any more, please leave their info in the comments.

And one more thought for anyone craving crispy chicken tenders. These are often made with reconstructed meat that has been triple coated with flavoring agent-encrusted protein isolates and refined flour, and deep fried (in toxic, oxidized vegetable oils). This is not just because food scientists are trying to make food addicting. It’s necessary to make up for the lack of scrumptious skin and fat cracklings that can develop with a well-baked bird. What I’m getting at is if you get quality meat and cook it properly, maybe you’ll like it even better.

Please link or share your roasted chicken recipes in the comments!

Further Reading

Quoted phrase on how sodium bicarbonate NaHCO3 helps disguise the colour, tenderness, and water distribution of raw and cooked marinated beef.

Poultry PSE rates between 7 and 43 percent and 70 percent.

Hiding the defects: No difference after roasting chicken breast. Other ways to use it.

A choice quote: “Although PSE pork has acceptable nutritive value and taste, some protein and vitamin loss occurs with the exudate.”

Insights from a CIA chef https://butcherinfoblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/pale-soft-exudative-pork.html

CORRECTIONS

As originally published the current US rates of PSE pork were listed as between 5 and 15 percent. Currently it is lower and the figure will be updated as soon as I get more accurate current data.

This Post Has 8 Comments

Note: Please do not share personal information with a medical question in our comment section. Comments containing this content will be deleted due to HIPAA regulations.

I thought I was the only one thinking, chicken tastes different. Well, its like eating rubber with all added spices.

Thank you for this article and since I don’t like the taste of meat, why bother buying it wasting time cooking, when you can just make something else.

As directed on the FAQ page, I’m posting a seed-oil related question here, since this is your latest post. I don’t buy many processed foods but have occasionally bought Simple Mills almond crackers which, I was sad to discover, contain sunflower oil. So I found the following on their web site and on Mark Sisson’s Daily Apple. What do you think about their assertions? (I’m making my way through Deep Nutrition right now – intense, but fascinating. Thank you for your work!)

https://simplemills.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/360020520713-Why-sunflower-oil-

https://www.marksdailyapple.com/is-it-primal-sunflower-oil-wheat-germ-skyr-and-other-foods-scrutinized/#axzz453viLaML

Please post on the Seed oil page, sorry if my instructions are confusing. Here’s the page to post the question if you would be so kind. https://drcate.com/seed-oils-questions-answers-for-your-health/

If I’m in a bind and need to buy meat from the store, do I look for sodium bicarbonate in the ingrefient list to determine if the meat is PSE?

Unfortunately if the meta is already in a precooked meal there is no easy way to tell, really. Sodium bicarbonate is also added to keep regular meat from drying out during storage and reheating.

This is why I breed my own Heritage chickens! I don’t trust most items from the grocery store. I buy all beef from a local farm that raises pasture raised, grass fed cows and I raise American Bresse chickens for our chicken. They free range from sun up to sun down and I only feed them the best quality organic, soy free feed. They taste delicious!!

I grew up rural south Philippines where I used to watch my mom slaughter chicken for the week. Now back living in the city, my mom knows where to buy heritage chicken and avoided the warehouse bulk chicken meat, warning me that those bulk chicken meat tastes “yucky”….. no wonder my son doesn’t like chicken meat at all!

But now, my son would eat the heirloom chicken I bought from Whole Foods.

Back in the mid-70s I worked for a computer company. One of my colleagues was a specialist in Management Science, which uses heavy duty math to optimize results. At the time there was a very large poultry company that was looking for computers to do least-cost feed formulation. The goal was to spend as little as possible raising the chicken, while maximizing growth and speeding time to market. Given the demand created by the ongoing world population increase, I am certain that little to no attention is being paid to the nutritional content of the birds raised this way. If my HOA would allow it, I’d raise my own chickens!